Karst is the landscape that contains caves

Karst includes sinking streams, sinkholes, springs, collapses and other features

Karst and California Caves

While karst is not a type of cave, it is key to understanding California’s caves. Karst is the odd term for some odd parts of the Earth. It is the German word (English is a Germanic language) for a region in Slovenia that has limestone, caves and many karst features. All karst regions are underlain by rock that dissolves such as limestone, marble and dolomite. When these rocks dissolve into streams flowing underground, caves form. But many other features can also form. And these features impact people living in karst. Water moves in its own unique way in karst, and the study of it is known as karst hydrology.

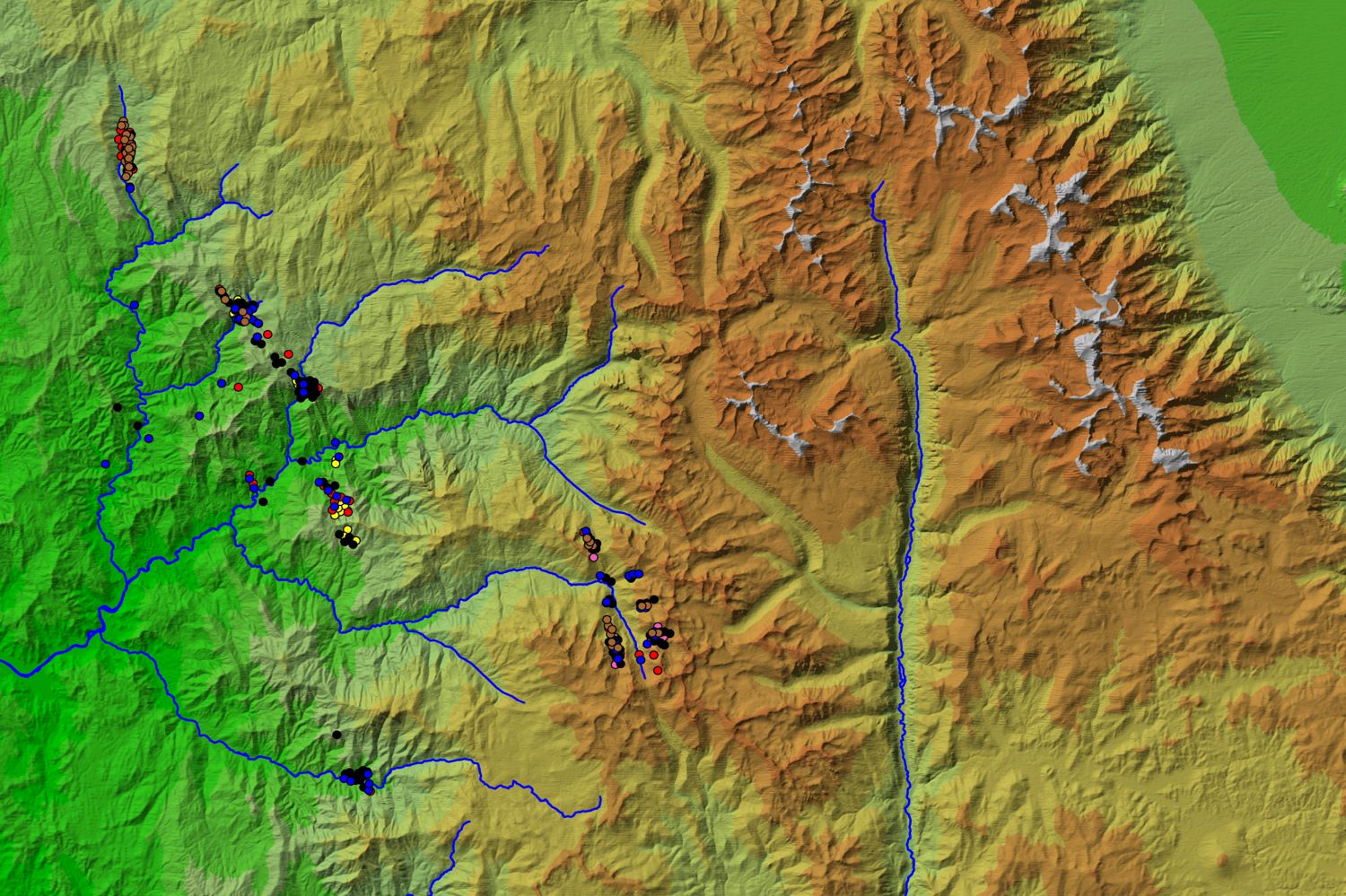

Where the water comes out of karst systems and caves, there are springs. Sometimes the water bubbles up from the base of a slope, other times it flows directly from the cave entrance or may even appear as a waterfall or steep cascade emerging from a cliff. Karst springs are found across the uplands of the state including in the Sierra Nevada, Coast Ranges and Klamath Mountains. In some watersheds, the springs account for a large percentage of the water found in the rivers at low, base flow, late in the summer and in fall.

Dr. Ben Tobin, Director of the National Cave and Karst Research Institute in Carlsbad, New Mexico, did his PhD studies on the karst springs of the Kaweah River Basin in Tulare County. He found that up to 88% of the water in the North Fork (one of five forks) of the Kaweah was derived from karst springs at base flows. Other forks had lower values including 43% for the East Fork and with an overall average of 20% for the entire river. This pattern is repeated in many other watersheds in California where caves and karst are located.

Some karst features form where the water goes underground. Most often, these are sinking streams or sinkholes. Sinking streams are creeks that rise and form in a valley on the surface, that are then diverted underground. Often, above the sink, the stream flows across rocks that do not dissolve, such as granite or schist in California. Once the creek hits the limestone or marble, caves begin to form and the water is channeled underground, forming and slowly enlarging the sink, although they are often clogged with rocks and sediments.

Where the limestone bedrock is not soil covered, most often in alpine areas in the Sierras or Klamath Mountains, an odd landscape can form. The nearly white rock is often eroded and pitted with deep, wide cracks. Strangely-shaped rock towers, arches and walls form. Sinkholes cover the ground and pits and collapses are common. On the surface and in the caves, the rock is often sharp and has deeply eroded cuts and channels known as karren. Traveling across these regions can be slow going and dangerous. This is known as alpine karst formed on the surface of the limestone.

Sinkholes are depressions in the Earth’s surface. These bowl-shaped divots are each a small internal drainage feeding water into cave passages below. Small ones are a few feet across, large ones are miles in diameter, and they often come in groups with many clustered together. In states like Kentucky, there are thousands of sinkholes making the landscape look like the dimpled surface of an enormous golf ball. In California, they are less common but still exist in many locations, such as the southern Sierra Nevada and the Marble Mountains.

The out-of-sight, underground streams in karst areas can flow in any direction, sometimes creating big problems for people. The water usually follows weaknesses in the rock that may lead, in what seems from the surface, to be unlikely directions. Because cave passages are open, the streams can carry pollutants long distances quickly. In the city of Bowling Green, Kentucky, home to Western Kentucky University, in the 1970s, parts of an elementary school erupted in flames on a Sunday afternoon. Luckily no one was there or hurt. The fire came from gas fumes rising from a cave below the school. Upstream a gas station had leaks in its tanks. The gas had traveled for miles floating on top of the water in the cave stream. Luckily, no similar accidents have ever happened in California. Sometimes it is best if out of sight does not lead to out of mind.